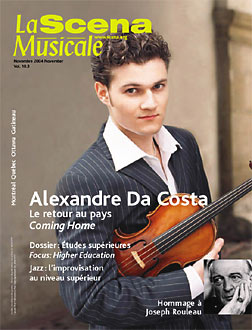

Violinist Alexandre Da Costa is coming back to Canada this month for a number of concerts and the release of a new CD of works for solo violin. This recording -- his fifth with Disques XXI-21 -- gives us a chance to hear, in all its splendour, the Baumgartner Stradivarius loaned to him by the Canada Council for the Arts. The new release includes Bach's Sonata No. 1 and Ysaye's Sonata No. 2, as well as André Prévost's Improvisation and Robert Lafond's Solitario, the latter being the title of the CD.

Born in Montreal Canada in 1979, Alexandre showed an uncommon interest for both the violin and piano at a very early age. By the age of nine, he had the astounding ability to perform his first concerts with stunning virtuosity on both instruments, which brought him recognition as a musical prodigy. After having won several first prizes at the Canadian Music Competitions, his international music career took off with recitals and concerts in Canada and the U.S.

In 1998, at the age of 18, Alexandre received a Master’s degree in violin, Premier Prix Concours, from the Quebec Conservatory of Music where he studied with Johanne Arel. Concurrently, he also received a Bachelor’s degree in Piano Interpretation from the Faculty of Music of the University of Montreal where he studied with Nathalie Pepin and Claude Labelle. From 1998 to 2001, Alexandre studied with the violin master Zakhar Bron at the Escuela Superior de Musica Reina Sofia in Madrid.In the course of his studies, Alexandre also attended master classes and extensive courses in violin with several other internationally renowned figures, including Sergei Fatkouline, Christian Altenburger, David Cerone, Jose-Luis Garcia Asensio, Shlomo Mintz, Pinchas Zuckerman, Mauricia Fuks, Maxim Vengerov, Vadim Repin, Martin Beaver, Herman Krebbers, Robert Masters, Gerhard Schulz and Rainer Honeck.

Da Costa's persevering approach has earned him major recognition from the Canada Council for the Arts who rewarded him with a three-year loan of a magnificent violin--the Baumgartner Stradivarius of 1689. "It's a fabulous instrument!" says Da Costa. "It is helping my career on more than one level. I now get more attention from some conductors who wouldn't have thought of me before. My previous violin, an 1842 Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume, was also a very good instrument, and worth far more than I could afford. Each violin has its advantages and disadvantages. For example, the two instruments differ in power. Of course the Stradivarius is now my preferred instrument. I'll certainly feel a bit sad to have to give it back at the end of the three-year loan! Contrary to what you might think, it's not an easy instrument to play. In Vienna, where I live, some of my friends were curious and wanted to try it. They were really surprised to find it difficult."

Although audiences don't often think about the way instruments get passed around, it is a reality soloists at the start of their careers have to reckon with. "At first I said to myself, 'Wow! A violin worth three million dollars!' I treated it with extreme care, left it at home, and so on. But it's my working instrument and I have to have it with me at all times, in the street, the metro, the plane, or coming back to the hotel after a concert. I come from an artistic background: my mother is a painter and my father is in the theatre. It's not a milieu where there's a lot of money, and I would never have been able to pay for an instrument that would enable me to make a career in music. Therefore, I started with a modern Canadian violin provided by a foundation, and that's what I took to Europe. My teacher introduced me to a number of people and eventually I was able to get a superb Ruggieri for six months. It had belonged to Yan Kubelik. Then I was lent a Balestrieri. Following a concert in Montreal, a music-lover decided to help and bought the Vuillaume in order to lend it to me. Then I entered the competition for the Canada Council instrument bank, and here I am with a Stradivarius [and a Sartory bow, lent by the Canimex Foundation, which Da Costa uses with one of the 300 varieties of string provided by the Thomastik Company]. Things move quickly in the music world!"

[...]

Two days later, he will appear at a benefit concert at the Salle Claude-Champagne in Montreal marking the twenty-fifth anniversary of the music program at Pierre-Laporte High School... and its possible disappearance! The prospect touches a sensitive nerve in Da Costa. "It was my school! The proposed cuts are, in my humble opinion, a cultural disaster, and I'm committed to defending the program that enabled me to develop and gave me the time and the environment to do research and pursue artistic excellence. It would be very sad to see this unique program abandoned. To shut down a program that is open to all, whatever their financial status, will also confirm a false belief, which is that classical music is only for rich people. It's just the opposite, and I'm a perfect example of this. The Pierre-Laporte School is one of the organizations, along with the Conservatoire de Musique de Montréal, that allowed me to get a top-ranking musical education that was financially accessible."

Notes on the Stradivarius Violins

Antonio Stradivari was born in 1644, and established his shop in Cremona, Italy, where he remained active until his death in 1737. His interpretation of geometry and design for the violin has served as a conceptual model for violin makers for more than 250 years.

Stradivari also made harps, guitars, violas, and cellos--more than 1,100 instruments in all, by current estimate. About 650 of these instruments survive today. In addition, thousands of violins have been made in tribute to Stradivari, copying his model and bearing labels that read "Stradivarius." Therefore, the presence of a Stradivarius label in a violin has no bearing on whether the instrument is a genuine work of Stradivari himself.

The usual label, whether genuine or false, uses the Latin inscription Antonius Stradivarius Cremonensis Faciebat Anno [date]. This inscription indicates the maker (Antonio Stradivari), the town (Cremona), and "made in the year," followed by a date that is either printed or handwritten. Copies made after 1891 may also have a country of origin printed in English at the bottom of the label, such as "Made in Czechoslovakia," or simply "Germany." Such identification was required after 1891 by United States regulations on imported goods.

Thousands upon thousands of violins were made in the 19th century as inexpensive copies of the products of great Italian masters of the 17th and 18th centuries. Affixing a label with the master’s name was not intended to deceive the purchaser but rather to indicate the model around which an instrument was designed. At that time, the purchaser knew he was buying an inexpensive violin and accepted the label as a reference to its derivation. As people rediscover these instruments today, the knowledge of where they came from is lost, and the labels can be misleading.

A violin's authenticity (i.e., whether it is the product of the maker whose label or signature it bears) can only be determined through comparative study of design, model wood characteristics, and varnish texture. This expertise is gained through examination of hundreds or even thousands of instruments, and there is no substitute for an experienced eye.

No comments:

Post a Comment